Writing, for me, is a process ripe for distraction. As William Zinsser said in “On Writing Well”:

A writer will do anything to avoid the act of writing. I can testify from my newspaper days that the number of trips to the water cooler per reporter-hour far exceeds the body’s needs for fluids.

Everyone deals with it differently. I like to physically remove distractions: phone, music, internet, until the only option is to sit and write. Even that sometimes is not enough — and the best remedy I have found is to have a separate machine just for writing. When I was writing “Junior to Senior”, it really helped:

I write on a very slow Linux computer that can’t play music, has no internet, and my phone is on silent, face down, in another room.

Why Linux? I like it, and on even the barest of Linux systems I can set up my usual note workflow — I use Neovim (or previously, Emacs) with a handful of plugins.

The “very slow Linux computer” was a 12.1” Lenovo ThinkPad X201. I love an old ThinkPad. The keyboard is great and they’re built to take a beating.

Writing on one made me think: this is great, how can I make it even better? The battery life on the ThinkPad wasn’t spectacular, and it wasn’t light. I also had to leave it behind when I moved. What would make a perfect writing computer?

- As small as possible without compromising touch typing. Below we’ll look at some machines that took it too far. The ideal screen size for me is between 7 and 10 inches.

- Battery life that gets you through the day. Three-four hours is too little — I sometimes spend more time than that on the train in one day. Six hours and more is better. Some machines will give you days of battery life (at the expense of functionality).

- A real operating system. Most of the time I’m not writing chapters for a book from a blank page, I’m working within my note archive: searching, referencing, cross-linking. I need a machine that would let me easily have the latest version of my note archive on it, and that likely means Linux — thankfully, Linux runs almost on anything.

- Weight is not that important, but around a kilo or less would be great. Definitely less than one and a half kilos. If I take this machine with me, I’ll probably have another laptop in my backpack. I don’t mind carrying the weight of a book, but not a brick.

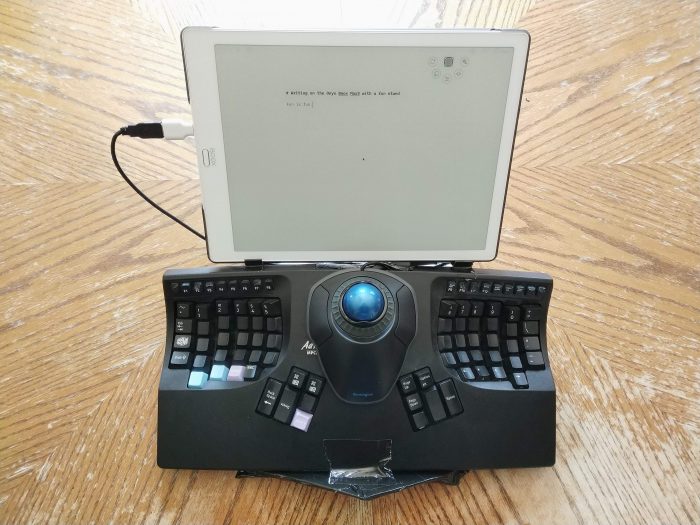

- I’d prefer it to be sleek rather than bulky. For writing, what would be more perfect than a tricked Kinesis Advantage with an e-ink screen? It’s portable in the sense that you can carry it, but that’s not what I’m looking for. I much prefer the laptop form factor.

- I’d like the device to have no moving parts. Today this is fairly easy with the advent of ARM — most ARM devices don’t have fans, and fans have been the last frontier; SSDs have made spinning disks obsolete many years ago.

- Price? All things considered, the value of such a device for me is not high. I can simply turn off Wi-Fi on my 13.3” MacBook Air M1 (that has no fans) and get 90% there. However, I love cool little machines and I’d be willing to spend quite a lot on something that ticks most boxes.

The perfect machine, then, would be a tiny ARM subnotebook with an e-ink or transreflective screen (for lower power consumption), a full OS and good battery life. Alas, no manufacturer actually makes them, for various reasons. There have been a few weak attempts, but there is nothing off the shelf — as far as I know — that you can buy, for any price.

Modern laptops fit the bill almost exactly, except that they are larger than I’d like. I could also probably live with something like an iPad mini and a Bluetooth keyboard, but it’s not cool, you know what I mean?

Among what actually exists I can see several categories of devices:

- consumer laptops (the most interesting segment that includes UMPCs, “cyberdecks”, netbooks, etc.),

- specialized writing hardware (the biggest drawback usually the lack of a capable OS),

- DIY “laptops” (e-ink screened Raspberry Pi jobs and other expirements),

- tablets in various configurations (modern tablets with integrated keyboard folios are technically no different from laptops).

Let’s look at a few machines I find interesting. (I’m sure there are a lot more than I mention below — I’d love to put them all in, but the post would be too long!)

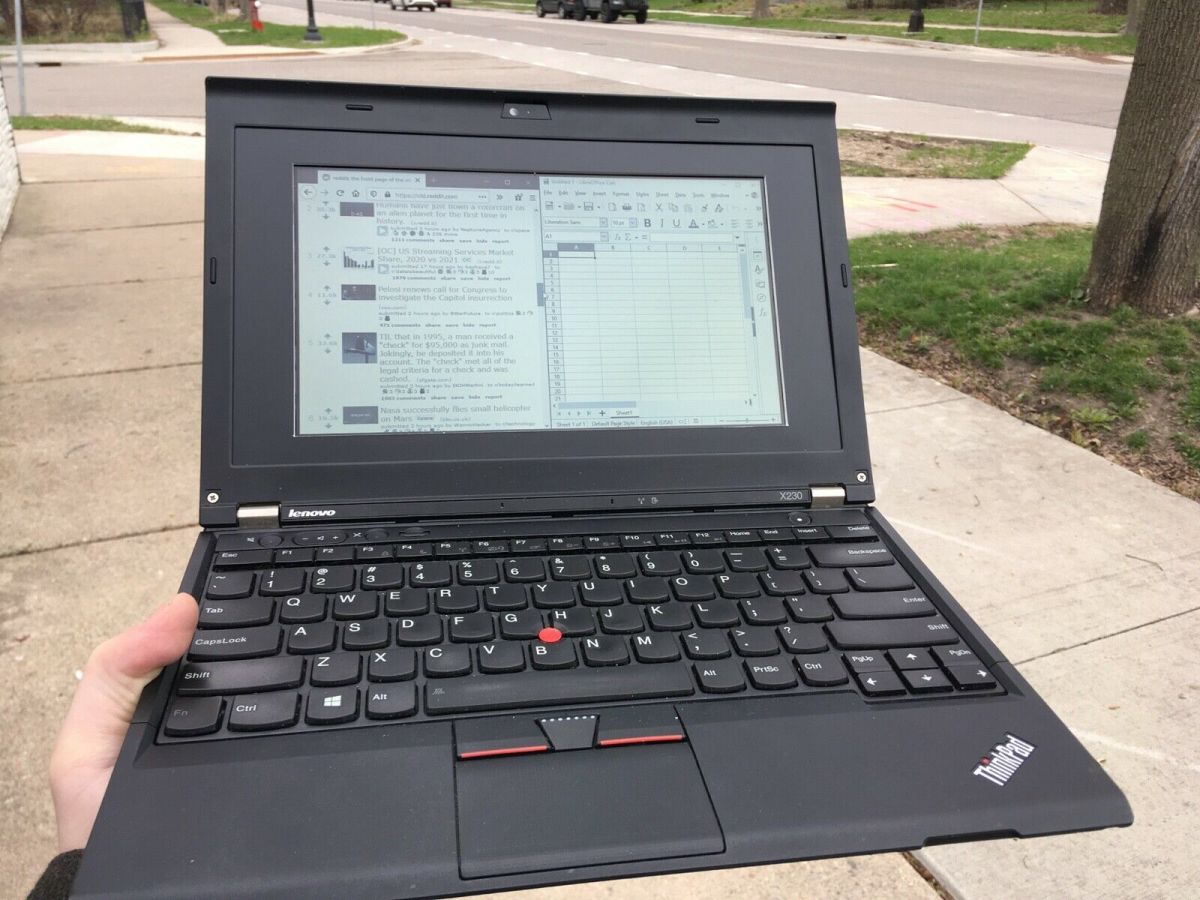

ThinkPad X230 with Pixel Qi display

Pixel Qi was a company that briefly produced a series of “paperlike” displays before the advent of large e-ink screens. They made their own laptop (impossible to find now) and display kits for several models of laptops. Some people fitted them to ThinkPads like you see above.

These screens are hard to find today, and the ThinkPads are too large, otherwise it would have been an attractive replacement. I rarely want to write outside (I’d rather take a walk), so for me the main benefit of such displays is low power consumption, not readability.

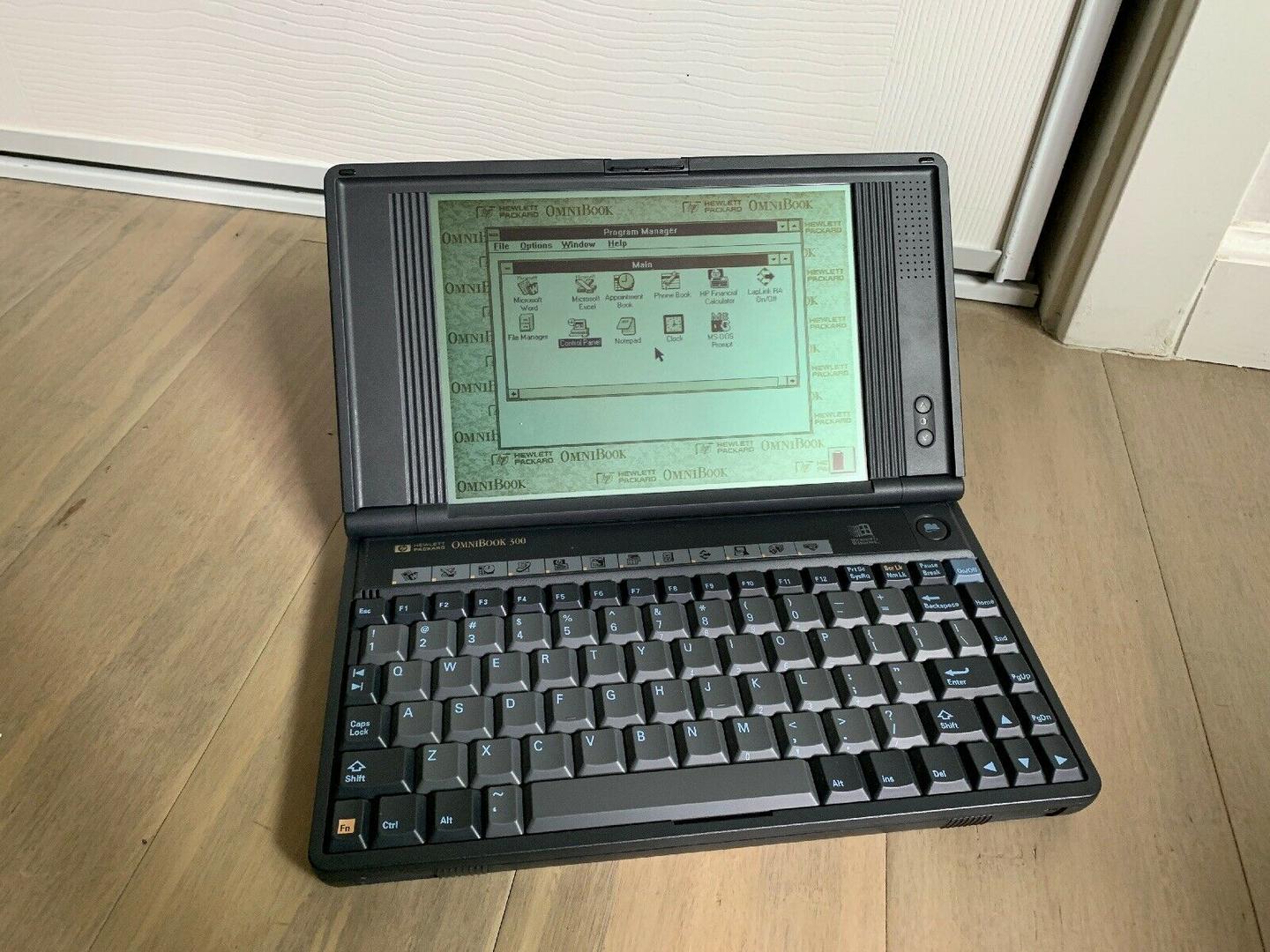

HP OmniBook 300

I first learned about the OmniBook 300 from Andrew Roach’s post and later saw a mention in Brian Lunduke’s newsletter. It was what sparked my original interest in a small and light writing device by showing what was possible. Released in 1993, it ran DOS or Windows off 4 AA batteries (!) for 9 hours (!!) with a 9-inch screen. It still looks sleek and modern — and I particularly like the keyboards of that era, that have not yet been flattened like in modern laptops.

I was seriously considering getting one, but it’s a bit too disconnected and underpowered for me.

There have been several other worthy “DOS palmtops”: Lexicomp Gradebook 2000, Tidalwave PS-1000, Atari ST Book, but on looks alone, the OmniBook 300 is the best.

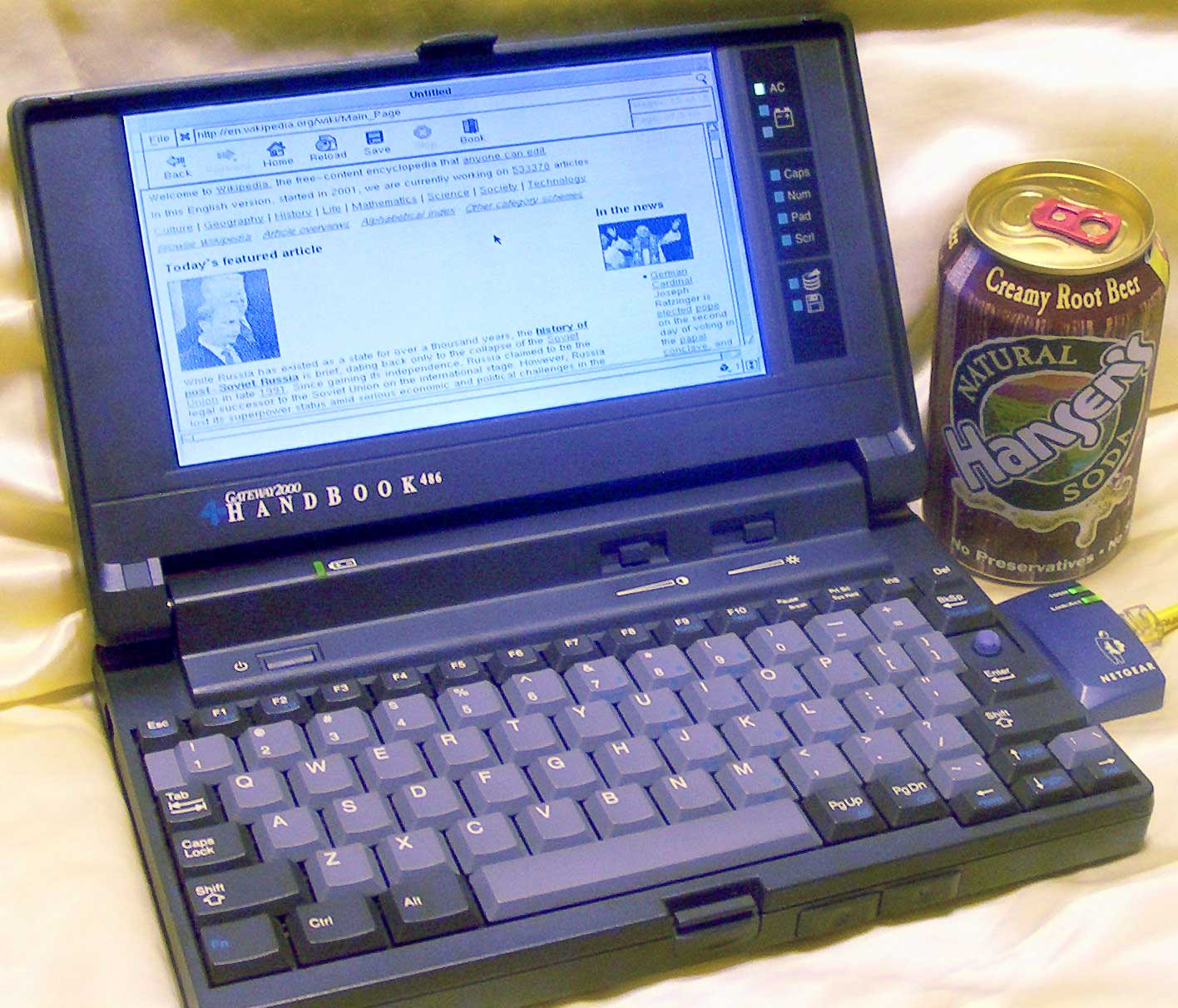

Gateway Handbook 486

The Handbook brings the 486 processor where the OmniBook had only 386, and is a wholly more capable machine not limited by the static flash storage. The battery life is worse, but you can install Linux and connect to the network through its PCMCIA slot.

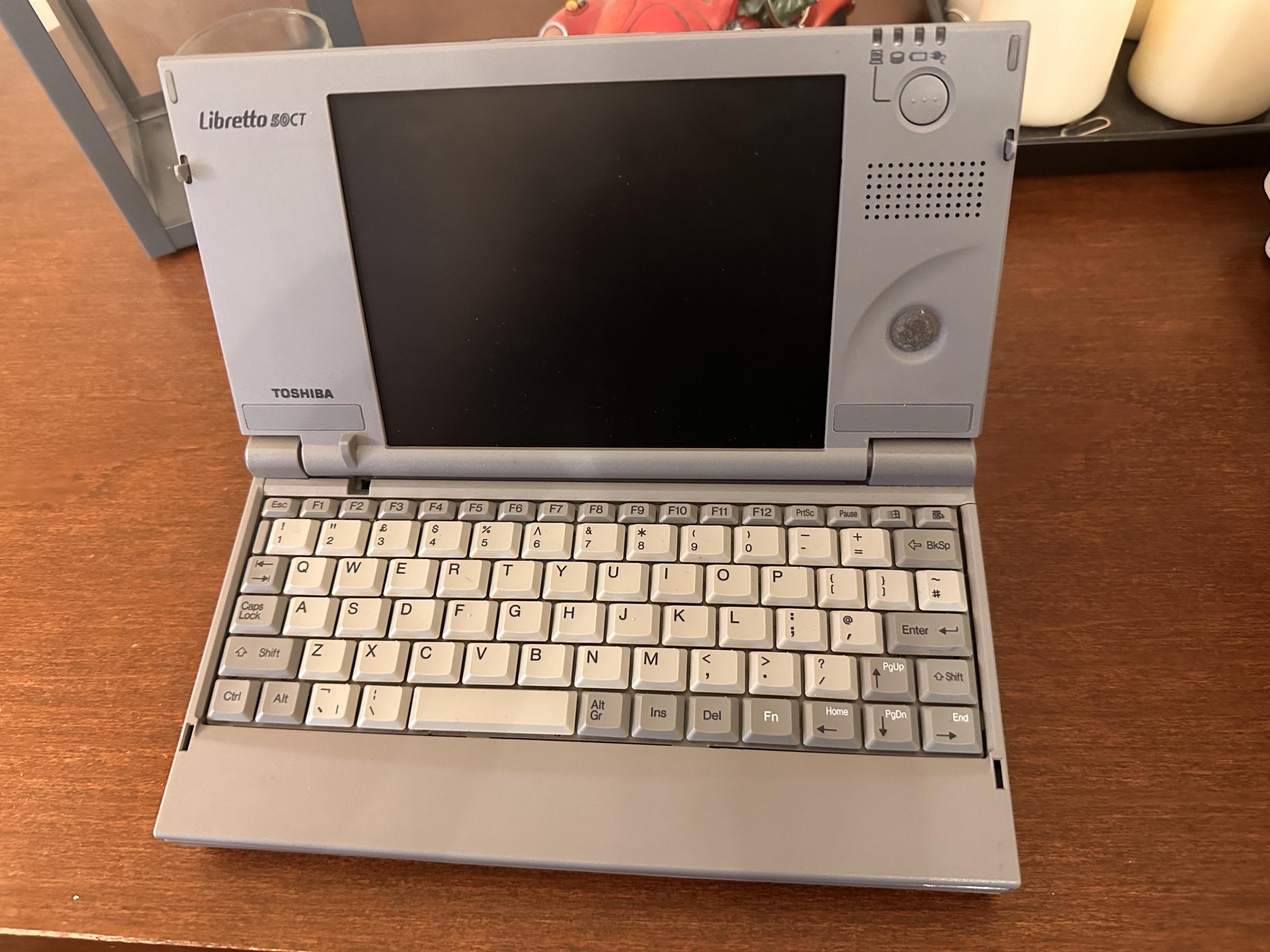

Toshiba Libretto 50CT

The 50CT is remarkable for its weight of just 850 grams, only 100 grams more than the original iPad. It can run Windows 95, but the battery life is too short: only a couple of hours.

Toshiba Portégé R500

This significantly more modern Toshiba weighs slightly under 800 grams (one review said “weighs almost nothing”). Even though the screen is 12 inches (too large!), the LCD is transreflective — it’s bright in direct sunlight and backlight can be turned off to extend battery life.

With a (claimed) 7-hour battery life, it would be a great contender, if not for its size.

GPD Pocket 3

Jumping to the present day, GPD Pocket 3 is seriously powerful with an 8-inch screen, and weighs around 700 grams. Because it’s a full-power laptop and tiny at the same time, it costs twice as much as a similarly-specced laptop of normal size.

With full power comes a big old fan, but the battery life isn’t bad at all at 8.5 hours. I simply don’t need such power, otherwise I’d definitely consider it — despite the price, it ticks all the boxes.

MNT Pocket Reform

7-inch screen, open hardware, open-source software, ARM, ortholinear keyboard — I just love the Pocket Reform as a concept. Not surprisingly, it’s quite expensive (even though not outrageously so).

What disqualifies it for me is the battery life of only about 4 hours, and the non-standard batteries. By contrast, both the full-size MNT Reform and MNT Reform Next (which are both too large) use sets of standard, easily replaceable 18650 batteries.

But doesn’t it look great? Probably it’s the ortholinear keyboard.

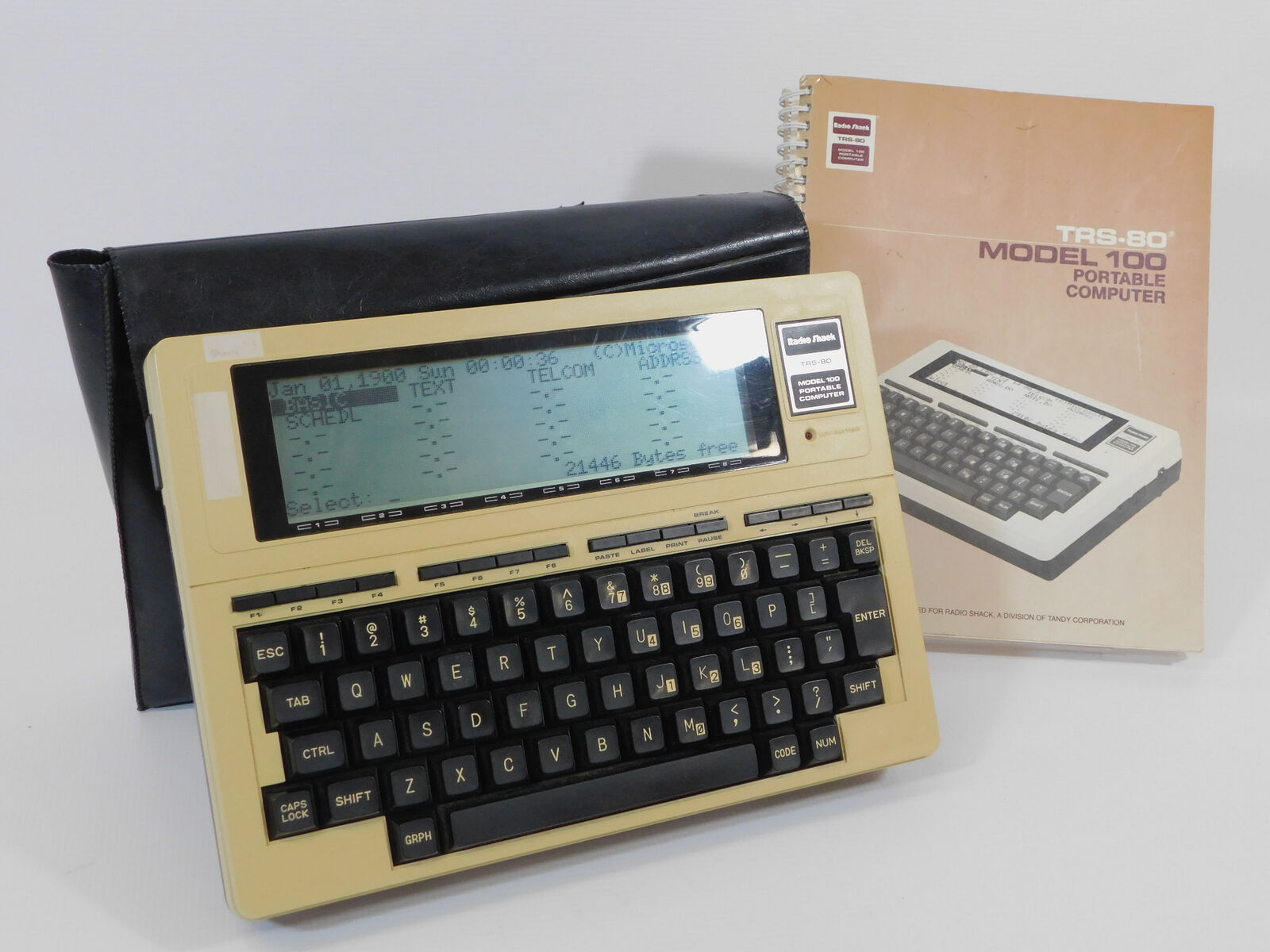

Tandy TRS-80 Model 100

This is definitely not a laptop, but still a portable — and comfortable — early computer. A 240 x 64 pixel display is enough for text, and it runs for 20 (twenty!) hours on four AA batteries. Even if your batteries died, an internal battery would still keep the files.

The slab form factor proved robust, and has been shared by both contemporary machines such as NEC PC-8201A or Amstrad NC100 and the modern versions — the Freewrite Alpha, AlphaSmart Neo and Dana (below) and a slew of cyberdecks.

The followup Tandy Model 200 looked like a laptop with the screen folding down, but was too large and much less popular.

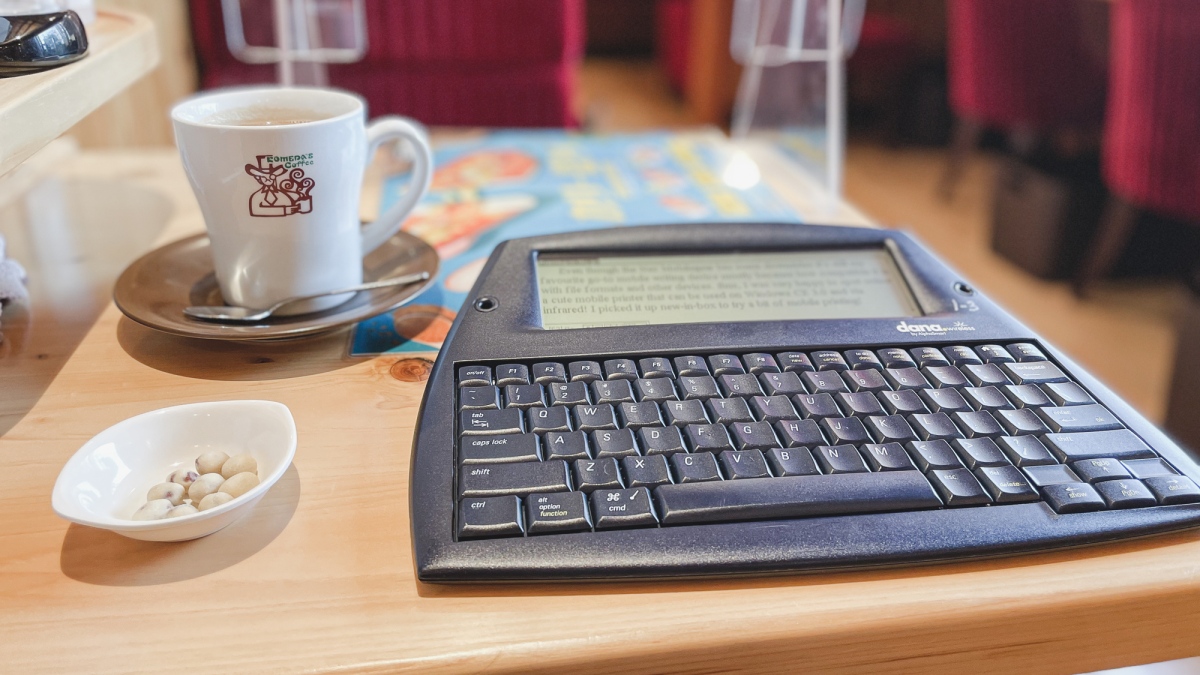

AlphaSmart Dana

The Dana has the same form factor as the Model 100 above, and none the less impressive. It runs PalmOS and has an excellent battery life of more than 20 hours from a modified set of AA batteries. (The simpler Neo model has a 700-hour battery life.)

You can still write software for PalmOS, if you want, and there is still a lot of software around. PalmOS is a joy to use — fast and efficient. An obvious device to mention is the Sharp Zaurus ZR-5000, but it’s not on my list because it’s too small.

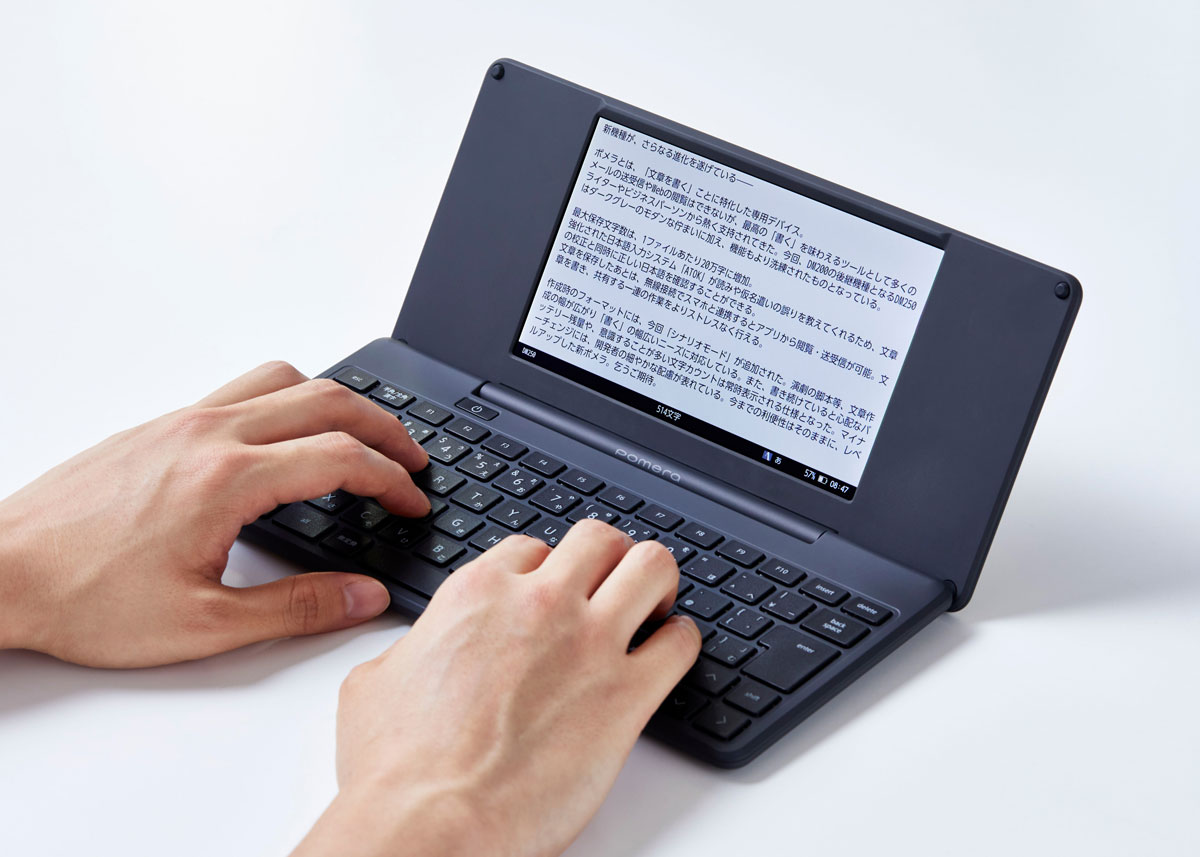

Pomera DM250

I learned about this neat little typewriter from jvscholz’s video “Tech I use to stay productive in 2024”. It’s designed specifically for writing and can manage a collection of text files.

A very neatly made device, however it only has custom software and costs quite a lot (around $600 new). Even if I wanted a write-only device, I’d rather pick up the Dana above — it’s more future-proof. Correction from a reader: it’s resold for a higher price, however in Japan you can buy it new for ~¥60,000 which is less, and it can run Debian — this makes it quite attractive.

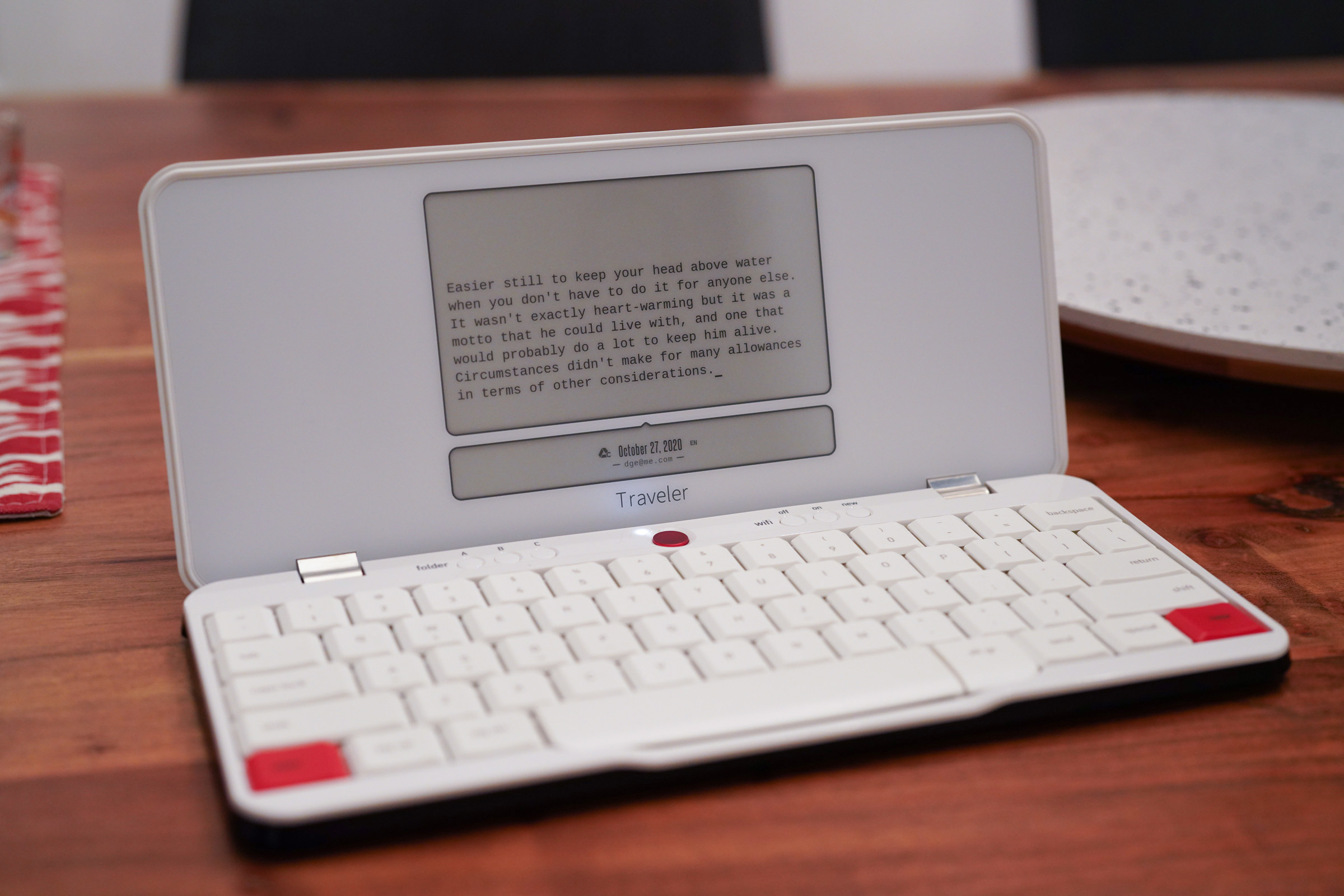

Freewrite Traveler

Another write-only (or as Freewrite themselves call it, “drafting”) device in the same niche as the Pomera. It’s expensive, neatly made, has an en-ink screen and an excellent battery life of 30 hours.

Both of these devices have long battery life because they use ultra low power chips and custom software designed to do one thing well (allow you to write and sync your writing to the internet). If they were powerful enough to run a full desktop-class OS, they wouldn’t work as long. It’s an easy choice if you only want to write! I’d pick up either of them if I wrote a lot.

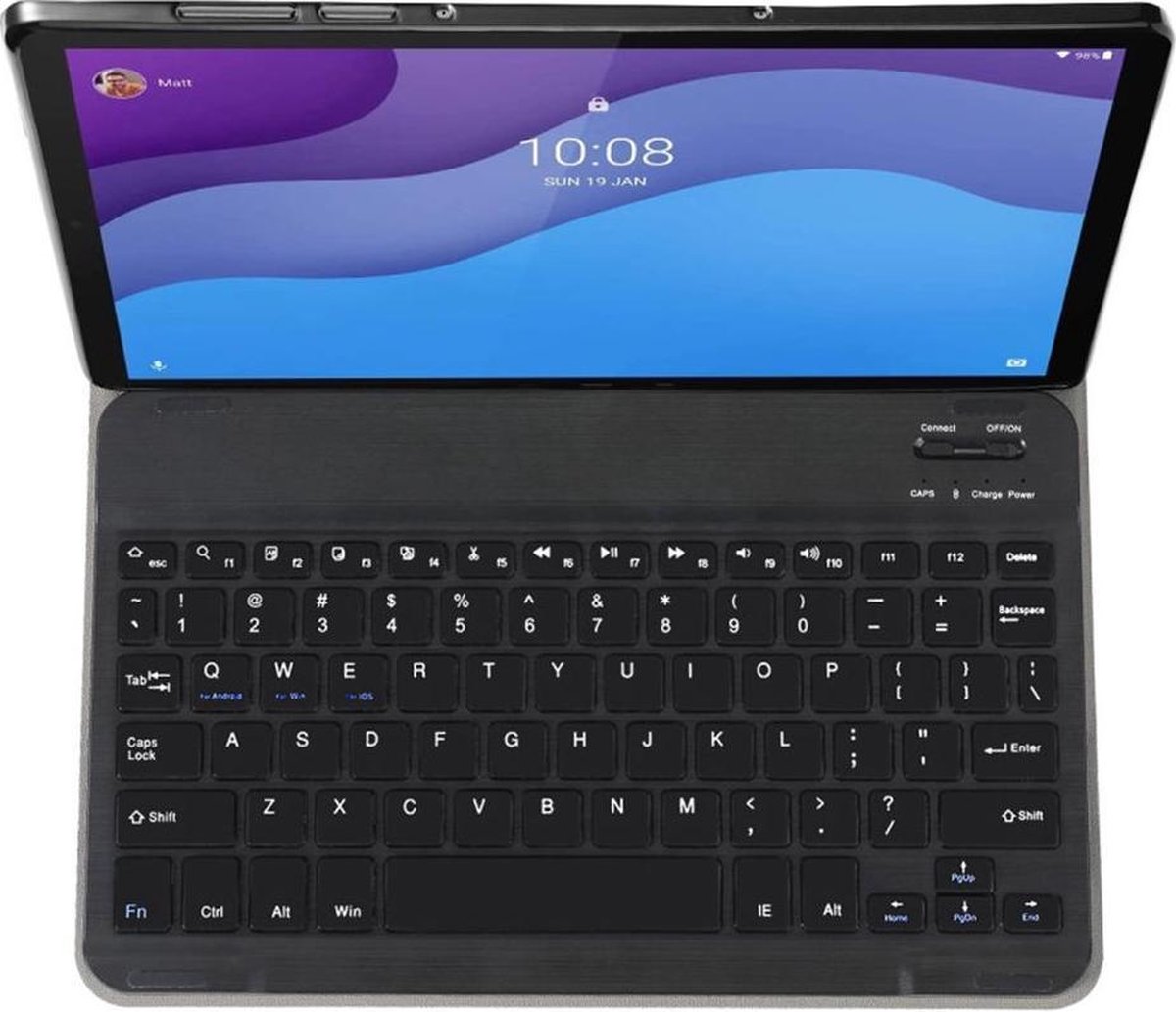

Lenovo Tab M10 HD 2nd gen

This Lenovo tablet, unlike the absolute majority of other tablets, can run Linux. Pictured above with a third-party keyboard folio, it becomes a little 10-inch Linux laptop with 8 to 10 hours of battery life and no fan noise (because it’s an ARM processor).

It’s cheap too. I almost bought it, but I like actual laptops too much… However, I highly recommend it if you’re looking for an ultraportable, ultralight Linux setup. With a powerbank, the battery life can be extended to 20 hours and more.

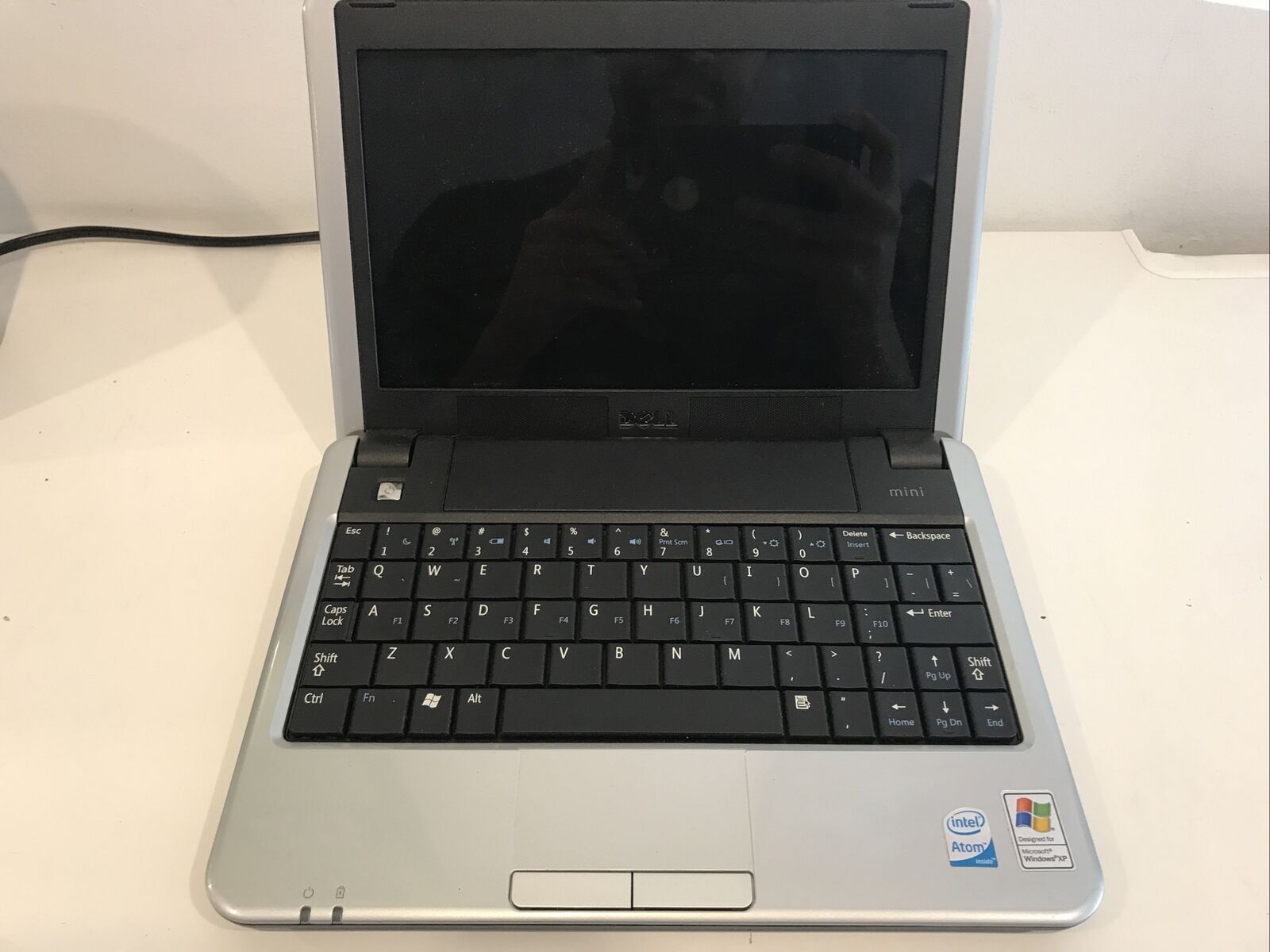

Dell Inspiron Mini 910

I can’t overlook netbooks because they are underpowered, small and run full OSes. They are also cheap. True, but all of them look bad, the Inspiron Mini 910 above not an exception. Put it next to the OmniBook above, and it looks like a poodle next to a wolf — all cheap, shiny plastic. Nevertheless, this is the one I bought. Why?

Most netbooks fail several of the portable writing machine criteria, because they have fans, fairly short battery life, and most don’t run Linux. But this Inspiron is different. With a 6-cell battery, I expect it will run for around 10 hours. It has fully passive cooling (no fans) and an SSD, so no moving parts. It runs Linux (in fact, it even shipped with Linux as a choice), but not only that, if you pop the bottom panel, you can replace the SSD, RAM, the Wi-Fi card and put in a WWAN card. It’s also very cheap.

With a 9-inch screen, sacrifices had to be made, and the keyboard layout is slightly shuffled. And no, I don’t talk about the missing F-row that is moved to Fn + home row — in fact, I quite like that. The “‘” button is at the bottom right, and the tilde is on the Fn layer. However, I’ve got used to strange layouts so this shouldn’t be a problem.

I’ll describe how it works in practice in a separate post. See you in the next one!